We often find ourselves recognizing today’s women for their achievements. N.C. Central University music professor Candace Bailey is doing something different.

Bailey is studying the women, particularly women of color, who lived before most of our grandparents were born. She’s learning about their lives through their music collections and reshaping preconceived notions along the way.

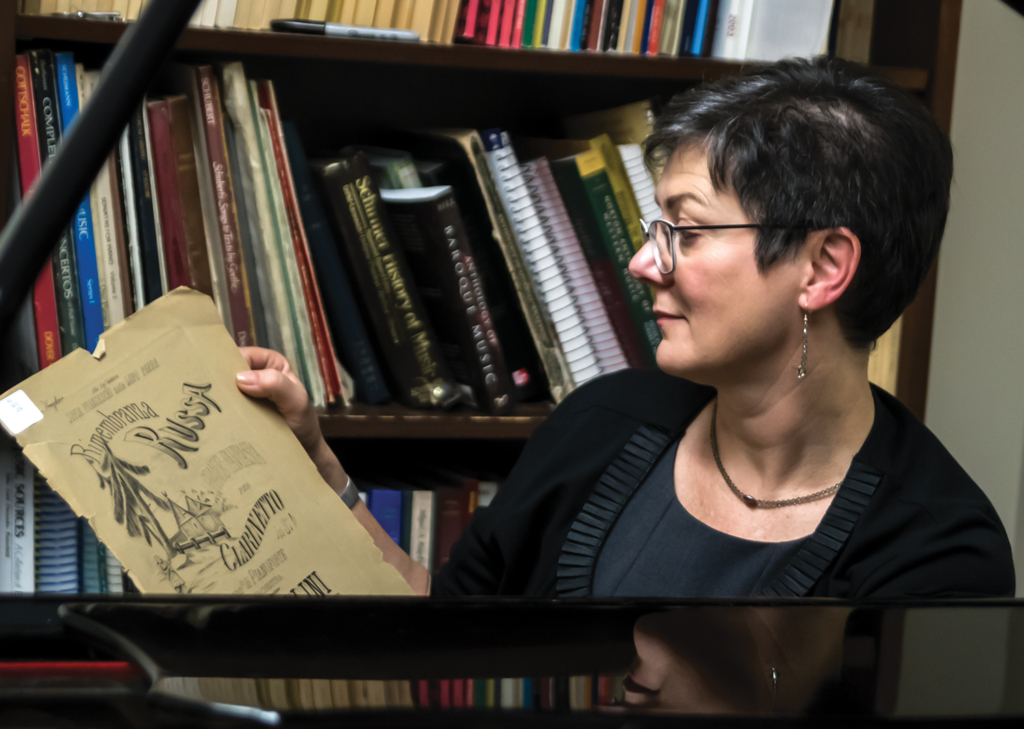

“I never know what I’m gonna find,” Bailey said.

Her love for the subject was set in motion when her father encouraged her to learn to play the piano, “so I could play in his weekend jazz band,” she said.

Bailey would go on to study music performance at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, though her father assured her there was no way she’d make a living as a performer.

After earning a bachelor’s in music performance, Bailey got her master’s and PhD in musicology (the study of music) from Duke University.

Bailey is also a member of the Society for American Music. Last year, she received the Judith Tick Award from the society, which provided her with funding to research women in American music.

She chose to study historical music because, she says, “history is my thing.”

She specializes in studying the music of women in the antebellum South, designated by historians to be the time following the War of 1812 and prior to the start of the Civil War. As you can imagine, music storage was done very differently during a time before streaming, CDs, or even record players.

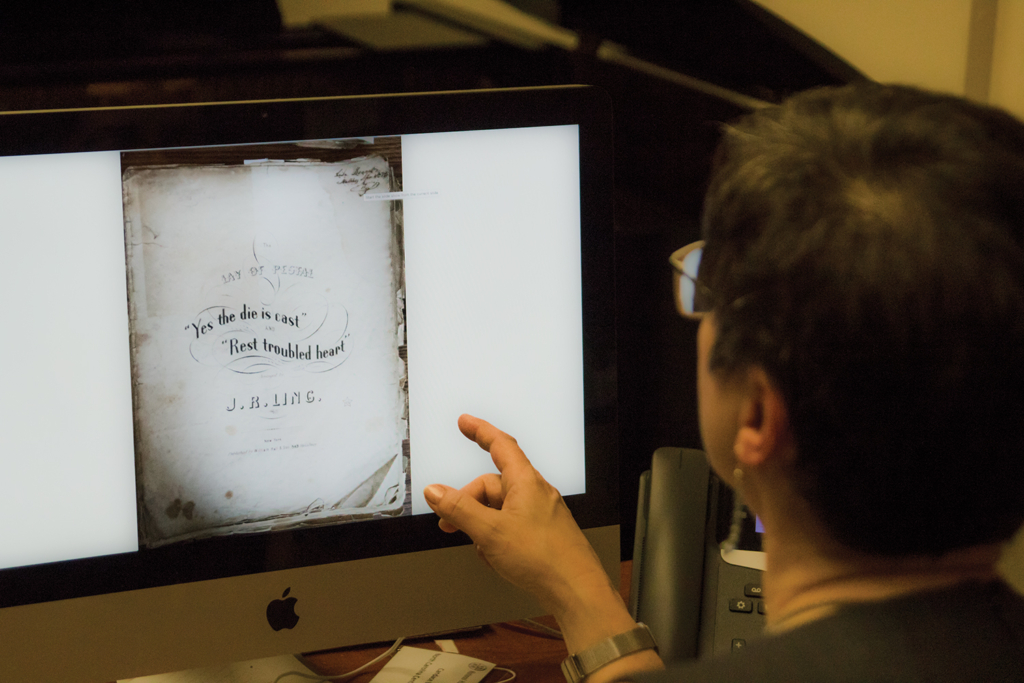

Now, these historical pieces of sheet music are preserved in libraries across the country. In 2015, Bailey received the National Endowment for the Humanities HBCU Faculty award, which came with a full year of financial support to do research. In that year, she went every month to a different archive around the South.

“I was at the Library of Congress a couple of weeks ago,” she said. “I finally got around to one of their research librarians who knew what I was looking for and managed to make it to where I could just take 20 at a time. They’d bring them out, and I’d look.”

Every time she finds a new collection, she photographs lots of documents, takes lots of notes and comes home ready to go through what she’s found. Throughout the years, she’s noticed a pattern.

“Women’s music, women’s stuff has been kind of pushed aside and put into boxes and put away. And men’s music in libraries gets put on display,” she explained.

To Bailey, these pieces of music can tell us a lot about the culture of women in the antebellum South. One of her most recent projects was studying the collection of the Johnson family. William Johnson was a highly successful African American farmer who had two daughters: Anna and Catherine.

The Johnson family archive was held at Louisiana State University’s Hill Memorial Library and contained both of the daughters’ collections, up to four bound binders’ worth of sheet music that had been put together by these free women of color.

“I found pieces that coordinated with the diaries, some of the friends’ names. So I was able to coordinate musical activities with the music in the volume,” Bailey said. “I was able to discern that they were guitarists, pianists, singers, that they continued music practice the rest of their lives. They never got married—they used music throughout life.”

Bailey said that discovering the musical activities of families like the Johnson’s challenges traditional beliefs about those who participated in musical activities.

“It’s not just middle class, which is what the history books tell you. And it’s not just the rich women, which is what we probably would have assumed,” she said. “But it’s women from a wide spectrum.”

Ultimately, she said, it’s not just about discovering the music of women in the South, it’s about the new questions raised by these findings.

“Who cares if we have 150 copies of this little podunk song? What’s more important, I think, and a lot of other people think, is how is music working in women’s cultural production? What it says about women and class.”