The war on drugs had erupted, apartheid was raging, Jesse Jackson would soon make the campus a staging ground for his inaugural presidential bid. Running for student office in 1982 at Howard University — the school that nurtured Thurgood Marshall, Toni Morrison and Stokely Carmichael — was no joke.

Sen. Kamala Harris (D-Calif.) has been known to break the ice with voters by proclaiming the freshman-year campaign in which she won a seat on the Liberal Arts Student Council her toughest political race. Those who were at the university with her are not so sure she is kidding.

It was at Howard that the senator’s political identity began to take shape. Thirty-three years after she graduated in 1986, the university in the nation’s capital, one of the country’s most prominent historically black institutions, also serves as a touchstone in a campaign in which political opponents have questioned the authenticity of her black identity.

“I reference often my days at Howard to help people understand they should not make assumptions about who black people are,” Harris said in a recent interview.

Her Indian-born mother and Jamaican father separated when Harris was 5, and she attended high school in Montreal, where her mother was a cancer researcher at McGill University. But, Harris said, as a teenager, there was no question about her decision to return to the U.S. to attend Howard.

“My mother understood she was raising two black children to be black women,” Harris said in the interview, a line she has often used to settle questions on the subject. Shyamala Gopalan Harris encouraged her daughter to go to Howard, a school her mother knew well, having guest lectured there and having friends on the faculty.

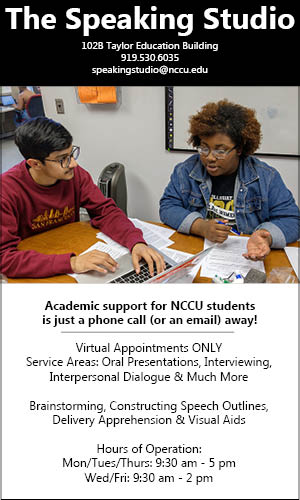

Kamala Harris graduated from Howard University in 1986. (Photo courtesy of Howard University.)

“There was nothing unnatural or in conflict about it at all,” Harris said. “There were a lot of kids at Howard who had a background where one parent was maybe from the Philippines and the other might be from Nairobi,” she added. “Howard encompasses the diaspora.”

The campus during her time was a cauldron of activism and black pride at a moment in history, like now, when most black Americans were feeling alienated and unrepresented by the White House.

Running for student office “was hard core,” said Sonya Lockett, a college friend of Harris. “It was not like, ‘If I win, we’re going to get a water fountain for the student center.’

“Students demanded to know how you feel about what is going on in this country, and where is our place in it,” said Lockett, now an entertainment industry executive. “We saw ourselves as integral to the city and the country and the world. If you did not have an idea of where we were in that ecosystem, you weren’t getting far.”

Campus politics were not always gentle. There were fights over where voting machines would be placed, and the hours they would be open. Student leaders tangled over how aggressively to confront a college administration perceived as too cozy with the Reagan White House.

With the campus located in a Washington neighborhood with a high crime rate and student safety a major issue, the student council race also marked the first election in which Harris, who would go on to become a prosecutor, had to confront the nuances of criminal justice.

While the Reagan administration pushed for expanded prosecutions, “we took a more … holistic look rather than demonizing people at a time when all of us kids were right there in some very impoverished surroundings,” said Jill Louis, a “line sister” of Harris’ when the two pledged the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority in Harris’ senior year.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, the writer, attended Howard a decade after Harris; at a campus event this month, he remarked that the school’s history weighed on him every moment he was there and continues to this day:

“You owe people things,” he said after rattling off an intimidating list of alumni who preceded him. “I will owe Howard until the day I die.”

Harris, whose parents took active roles in the civil rights movement through the 1960s and into the 1970s, was familiar with the spirit of activism. But not on the scale of Howard, with so many black intellectuals and activists and future leaders all in the same place.

“We are talking about thousands and thousands of people,” she said. “It was extraordinary.”

When you go to Howard, said longtime Howard political science professor Alvin Thornton, your particular ethnic makeup was irrelevant.

“You were black,” he said. “Not physically. You were black in terms of your sense of responsibility and social relations of what we were trying to overcome. It was a sociological phenomenon as much as a physical phenomenon. It represented change and one’s commitment to it, or not.”

“I very much see Howard in her,” Thornton said of Harris. “These young people come into a culturally and academically reinforcing environment that enables them culturally. They can feel comfortable. They don’t have to question their identity, only grow into it.”

At her freshman orientation, Harris recently told a group of black female entrepreneurs, she was overwhelmed by the sense of possibility upon walking into a giant auditorium packed with overachieving people of color.

“You then are in an environment where everything tells you that you can be great, and you will be given the resources and expectation to achieve that, and the only thing standing in the way of your success will be you,” she said. “You don’t have to be limited by other people’s perceptions of who you are.”

Harris was known on campus, but she was not among the most prominent student leaders. Many of her classmates have more vivid memories of Christopher Cathcart, the hard-charging football player, now a communications consultant, whose tenure as student government president was defined by confrontation with the school administration.

Thornton, who headed the political science department’s undergraduate program, now jokes that he is frantically searching his records and jogging his memory for anecdotes to allow him to claim credit for nurturing the political acumen of Harris, who majored in his field, along with economics.

Those who knew her then say much about Harris on the campaign trail is familiar.

Ever since she became omnipresent on the television news, said Louis, her own father has remarked that the senator seems to laugh a lot.

“I told him, ‘That was her,’” Louis said. “She was always the person who seemed serious while not taking herself too seriously. … Before the bright lights, she was the exact same person we see today.”

Harris would take ribbing one moment about her cropped haircut and coat with the pointy collar that called to mind Peter Pan, then would be tearing an opponent to shreds on the debate floor the next.

“The one thing I can always remember about Kamala is that she was always friendly and the nicest person, but in a debate, it was almost like a switch was turned,” said Charles Boyd, a Detroit surgeon who attended Howard with Harris.

Others recall her certainty about her eventual career. Harris entered Howard wanting to follow in Marshall’s footsteps and never wavered in her pursuit of going to law school.

“There was no question about whether or not she would go,” said Shelley Young Thompkins, the fellow student council rep whom Harris calls out in her biography as the toughest opponent she ever faced. “There was zero wavering on that.”

It was not always an easy path. Harris got recruited for the male-dominated debate team by the one woman who was on it at the time, Lita Rosario.

“It was a very tough crowd,” said Rosario, now an entertainment lawyer in the Washington area. “I was one female who got through, and I thought she might be able to as well. She had spunk.”

As for campus activism at the time, Rosario said, “There were people who were more militant and wanted to do more extreme things, and others who felt taking over the administration building and asking for the university president’s resignation were not necessary, but still felt the need to do things.”

Asked where she landed on that spectrum, Harris sidestepped, as she often does with politically fraught biographical questions. She talked instead in more general terms about the high calling of student activism.

It is unclear, for example, the extent to which Harris was involved when students successfully demanded the reinstatement of a student newspaper editor who was expelled after raising uncomfortable questions about a sex discrimination complaint filed against the school. She was undeniably in the mix, however, when busloads of students went regularly to the South African embassy and the National Mall for protests demanding an end to apartheid.

“It was outrageous,” Harris said. “Mandela was in jail, and there were huge atrocities happening. The [Reagan] administration was not engaged in any meaningful way.”

Protesters were constantly arrested, including Jesse Jackson’s daughter, Santita, who studied at Howard when Harris was there. She was hauled off to jail the year after Jackson electrified the campus with his first presidential run in 1984.

“When Jesse ran, I would say the entire campus was behind him,” said Cathcart. “This was the first time many of us were voting in a presidential election, and for the first time there was a black candidate who we thought had a chance.” There were registration drives, canvassing events and viewing parties when Jackson spoke at the Democratic National Convention.

During those years, Harris’ classmate Boyd recalls, he “literally felt that I was at the center of black political thought. Anyone who was of note came to Howard to speak.”

And when Harris announced she was running for president, her first stop on the campaign trail was Howard.

She has since framed the Howard legacy as a relay race of black achievement. The question that has weighed on her during and since those years, she said in a recent campaign stop in Las Vegas, “is what are you going to do with the time in which you are carrying the baton?”

Story by Evan Halper

L.A. Times (Tribune News Service)