Body odor.

When we notice that unmistakable stench on ourselves, most of us rush to roll or spray on some product. But the fact is, there’s more going on in our armpits than meets the nose.

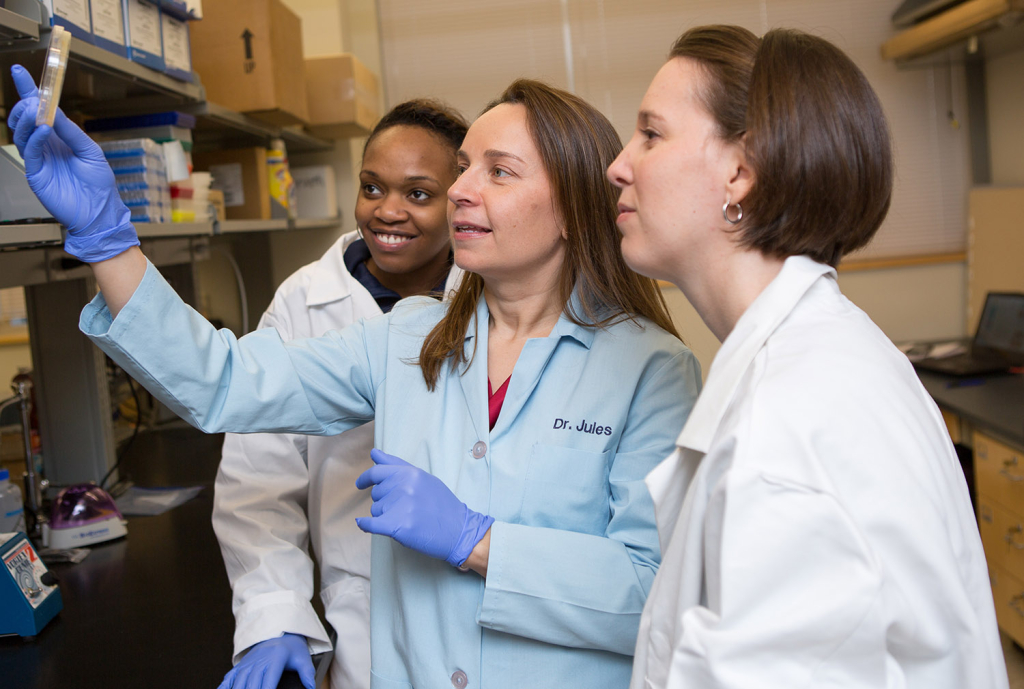

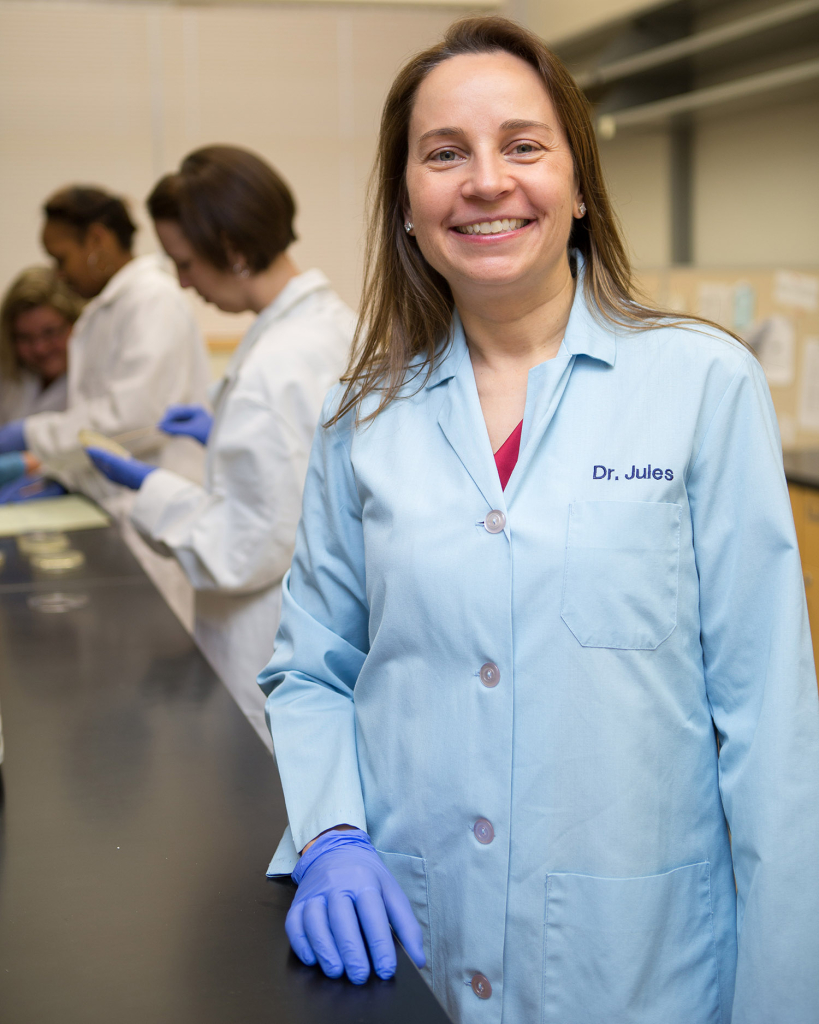

NCCU biology professor Julie Horvath is researching the most pungent areas in human anatomy. She’s looking at the microbes in the human armpit and how products like deodorants and antiperspirants affect their growth.

Horvath, the head of the genomics and microbiology research lab at the N.C. Museum of Natural Sciences, got into the “microbe business” via primates.

She was interested in comparing regions of the human genome to regions of primate genomes. The genome is a full set of chromosomes — nature’s instruction manual — which guides the development of all living things.

She wanted to see how humans and primates compare, but through the lens of our genomes.

This interest in primate genomes brought her to Duke University, where she studied lemurs.

“That sort of got me in the intermix of understanding how we can learn about ourselves from studying other species like primates,” Horvath said.

Horvath spent some time at Duke before being offered her joint position at NCCU and the Museum of Natural Sciences. With this new position came a new focus.

“Now there was a greater call to engage students and professors in research,” she said.

It had been harder before to engage others in her research, because she was working with live animals. Focusing on microbes (which can be observed and grown in a lab) paved the way for more public involvement.

Back to microbes, though. Microbes are microscopic organisms. They crawl around on your skin, feed on your sweat, and produce body odor.

It’s gross. But it’s true. Horvath compares microbes to something a lot more familiar.

“Right now, you can think of your skin as this healthy ecosystem, “this forest,” Horvath said.

And each armpit’s ecosystem is unique. In other words, my armpit may have a different makeup of microbes than yours.

According to Horvath, one explanation for this variation is the use of hygiene products.

Most people are familiar with the purpose of deodorants and antiperspirants. They fight body odor. But they do it in different ways, Horvath explained.

While deodorants have chemicals that kill or inhibit the growth of odor-causing microbes, antiperspirants prevent your armpits from sweating. This cuts off the food supply of microbes. No microbes, no stank.

With this idea in mind, Horvath set out to see how using these products affect microbe growth differently.

“We swabbed everybody working in the lab and looked at what was growing on them,” she said.

Then Horvath noticed something interesting about her own armpit sample.

“My plates were empty; there was nothing growing,” she said. “It freaked me out a little bit. But it got us talking about why there was no growth on my plate.“

The lack of microbes was traced to her antiperspirant use, Horvath explained.

“Because of this new position, I started wearing clinical strength antiperspirant,” she said. “I didn’t want to be the armpit microbe biologist who actually has body odor, right?”

In order to further investigate what these products do to the tiny ecosystem in our armpits, Horvath and her team launched an eight-day experiment.

Twenty people were divided into three groups: deodorant wearers, antiperspirant wearers, and non-product-wearers. The final results only include 17 people, however, due to illness and other constraints.

The first day, participants went about their usual routines. Then they were swabbed and their samples analyzed to see what microbes were growing.

On days two through six, all participants were asked to stop wearing any products, and were swabbed daily to check for the growth of microbes.

During the last two days of the experiment, every participant wore antiperspirant. This was to see examine antiperspirant’s effect on the growth of microbes in participants, Horvath explained.

“If we think that antiperspirants are inhibiting the growth of microbes, and we take it away, and microbes grow back. Then we can hypothesize that the antiperspirant is likely inhibiting the growth of microbes,” Horvath said.

When the experiment was over and the aroma cleared, Horvath and her team drew a few conclusions, according to their research, published in PeerJ.

They confirmed that antiperspirant use drastically decreased the number of microbes found in participants’ samples.

They also found that when participants stopped using products, their microbe density, or the amount of microbes in their samples, increased to levels similar to those who had never worn products. Essentially, the microbes made a comeback.

But, some grew back faster than others, Horvath explained, which changed the diversity of microbes in the samples.

“When you use product, you can imagine that it’s kind of like a forest that’s just had a fire,” Horvath said. “When you look back at this forest, you can see which organisms will grow back faster than others.”

Unfortunately for the microbes, unlike real forests they don’t have the benefit of a Smokey the Bear campaign. We wipe out these microorganisms often without batting an eye.

This is not to say that we should stop wearing deodorant or antiperspirant just yet. But microbes play an important role in our bodies, and deserve our consideration, Horvath said.

“A lot of the things you do on a daily basis might actually affect your well-being and you don’t think about it,” she said.

Although Horvath’s research has focused on things small in size, she maintains her big mission: engaging students and the public in science.