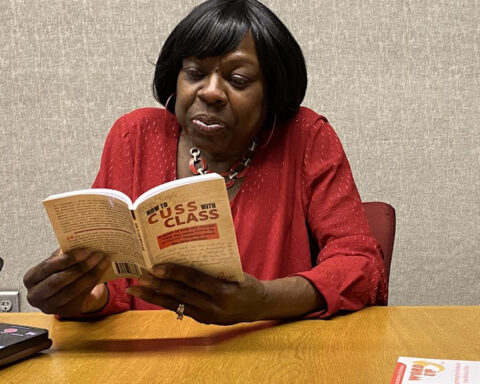

Dr. Claudrena N. Harold, the associate dean for the Social Sciences and Edward Stettinius professor of history at the University of Virginia, said she has come to appreciate gospel during the 2025 McNeil African American History Month Lecture on Feb. 20.

“I feel a deep connection to the people that I write about, sometimes it’s too much of a connection,” Harold said. “There is nobody I don’t feel deeply about. It has had a profound impact on who I am, even when I don’t like some of the messages.”

The event is usually hosted in the Sonja Haynes Stone Center for Black Culture and History at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill but pivoted to a Zoom webinar due to inclement weather conditions.

The webinar began around 7:15 p.m. The first four speakers were a series of UNC-Chapel Hill administrators, Dr. LeRhonda S. Manigault-Bryant, Dr. Marcus Collins, Dr. Miguel La Serna and Dr. Claude Clegg, who introduced Dr. Harold.

Harold is also the author of three books: “The Rise and Fall of the Garvey Movement in the Urban South, 1918-1942,” “New Negro Politics in the Jim Crow South” and “When Sunday Comes: Gospel Music in the Soul and Hip-Hop Eras.”

These three books share common themes, which she also highlighted in her speech, were Black political mobilization, the intersection of religion and politics and the Southern roots of Black liberation.

In her speech, “Truth is on the Way: Gospel Music, Black Liberation, and the Politics of Freedom in the Soul and Hip-Hop Era,” Harold said that “Hampton,” a movie about a choir at UVA, was inspired by a conversation she had with Debra Saunders-White, NCCU’s first female chancellor.

“She told the story of Being a student at the UVA in the 1970s and having this transformative moment and finally feeling like she belonged,” she said.

Harold’s speech also explored the political evolution of gospel music through the last 50 years. She focused on Dr. Wyatt T. Walker’s idea that what Black people sing in gospel music is a reflection of their sociological ideations.

She spoke of gospel artists through different eras and how they used their platforms to send powerful messages to their listeners.

Harold said Aretha Franklin’s music and political activism must be understood within a broader context of Black community struggles and liberation. She used Franklin’s 1987 recording of “Surely God is Able” and her “Amazing Grace” album to demonstrate how gospel music was intertwined with Black Power movements.

Similarly, during the Civil Rights Movement, the gospel group Rance Allen and the diverse singer Shirley Caesar used gospel music to talk about racism, class and poverty as they related to Black Americans.

Following this, Harold shared that her uncle, David Crawford, mentored her and posed questions that she still thinks of today.

“Was God’s word enough for the unique challenges of the post-civil rights, post-segregation, post-colonial, postmodern world,” Harold said. “Could and should gospel music provide more than Christian-based theological reflections?”

Around 8:30 p.m., Harold wrapped up her lecture with a riveting showing of a short film she co-directed with Kevin Jerome Everson titled “Dooni,” a film about a eulogy of the soul-singer Sylvester told by preacher and gospel singer Edward Hawkins.

“In ways both subtle and direct, these artists invite us to consider a different use of Black churches and the gospel imagination,” said Harold. “And that’s what I’ve attempted to do in a new experimental film with Walter Hawkins and Sylvester.”