Five former Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Civil Rights activists talked about their experiences in the 1961 Southwest Georgia Project during the peak of the Civil Rights Movement. The activists— Faith Holsaert, Shirley Sherrod, Larry Rubin, Annette White and Janie Rambeau – addressed a group of about 50 students and faculty on Saturday, Feb. 4 in the Alfonso Elder Student Union.

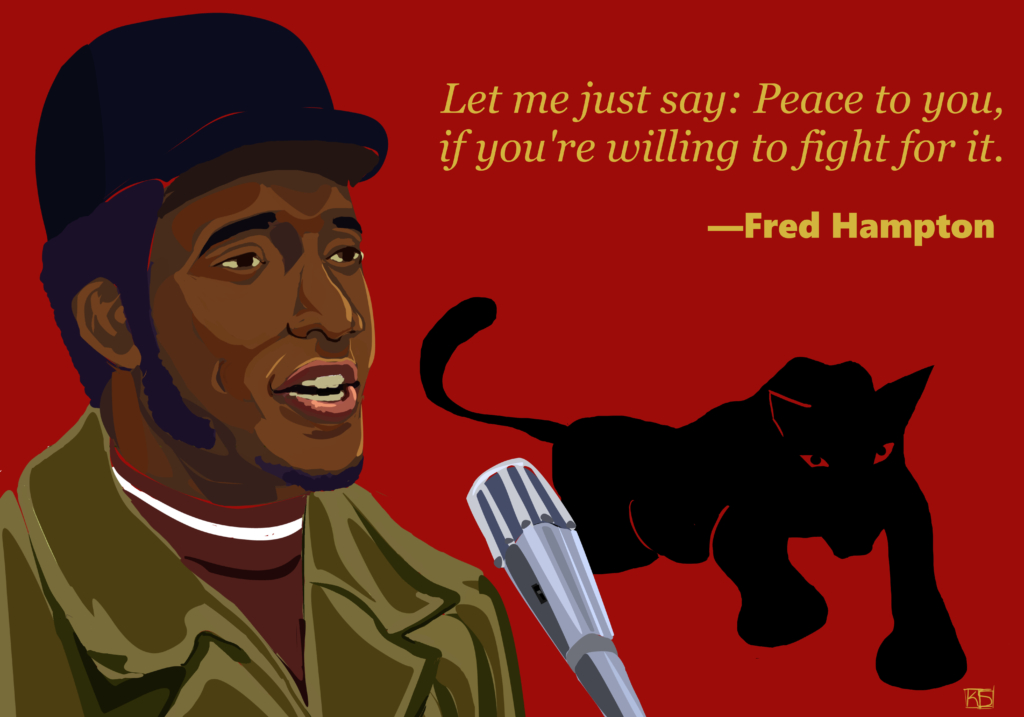

SNCC, founded in 1960 by Ella Baker at Shaw University in Raleigh, was launched after younger blacks felt that Dr. Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) methods were too passive and ineffective. SNCC leadership pushed for a more participatory strategy.

The Southwest Geogia Project was engaged in a number of activities, including voter registration, fighting for housing, and welfare rights. It was important in the history of the Civil Rights Movement because it was a largely integrated effort up until the late 1960s – activists Holsaert and Rubin, are both Jewish and from the North.

“The Southwest Georgia Project is both the most distorted and ignored movement in the South,” said Charlie Cobb, the panel facilitator and a former SNCC member himself. Cobb is currently working on a book, “Getting in the Way” that explores current social movements including “Black Lives Matter,” “Dream Defenders,” and the North Carolina “Moral Monday” protests.

“Southwest Georgia Project was people, hundreds of people, in this whole area working,” he said. “It was a more integrated project than any other SNCC project.”

Holsaert and Rubin explained why they – two Northern Jews – joined the Civil Rights Movement and signed up for the Southwest Georgia Project.

“I really didn’t join the movement until I went to Southwest Georgia and I saw people there risking their lives … being ran off their land … their houses burned down,” said Rubin. “They were being beaten up for exercising their American rights. I learned that part of my job was to move up in this community and to show people that blacks and white could work together and whites did not have to be in charge.”

Holsaert said she entered the movement convinced that “the good people were us.”

One county in the Southwest Georgia region, Baker, was known for its long history of racism and brutality to blacks. SNCC organizers even labeled it “Bad Baker.” It’s where panelist Shirley Sherrod’s father was shot and killed in 1965 by a white farmer in a dispute over cattle.

“I needed to think of what I could do,” said Sherrod. “A thought came into my mind. You can give up your dream of living in the north or you can stay in the south and devote your life to working for change,” Sherrod said.

As it turned out her future husband, Charles, had nearly been beaten to death a year earlier outside a Baker county hardware store by whites with wooden axes. Charles Sherrod, an ordained minister and member of the Student Interracial Ministry at Union Theological Seminary in New York City, was an early organizer of the Southwest Georgia Project.

“We had some notorious sheriffs from Baker County, one called Screws,” said Sherrod. According to Sherrod, Sheriff Claude Screws and his deputies beat a handcuffed black man, Robert “Bobby” Hall, to death in the 1940s. Hall had allegedly stole a tire and resisted arrest. But Screws wasn’t even charged with murder, just with depriving the civil rights of a black man.

Screws was first convicted, but the U.S. Supreme Court overthrew his conviction on the basis of “proven intent.” In other words, his conviction was overturned because the prosecutor failed to prove that Screws was intentionally depriving him of his civil rights while he was murdering him.

During the Obama administration Sherrod would become Georgia’s U.S. Department of Agriculture director of rural development, a position she was forced to resign from after far-right blogger Andrew Breitbart selectively edited a video of her speech to portray her as biased against whites.

One J.D. Clement Early College High School student at the event asked the panelists what millennials could do to help bring about change.

“If it were me I would get more into education,” Annette Jones White said. ” I always thought we had to start at the bottom because that’s what I did with my kids.” Somewhat ironically, because of her activism with SNCC and the Civil Rights Movement, White lost her 1961 title as Miss Albany of Albany State University, an HBCU.

The panel was sponsored by the SNCC Legacy Project, the Center for Documentary Studies and Duke University Libraries.

“The SNCC digital gateway project is really about telling movement history from the inside out; people who were in the movement are telling the history of the movement as they saw it,” said Karlyn Forner, SNCC digital project manager for Duke Libraries. [See a clip of Forner discussing the digital project and the panel discussion].

Freshman Kennedy White said listening to the panelist inspired her. “I didn’t know what to do to help my generation,” she said. “Listening to these veterans inspires me to actively participate in other movements.”

Written by Echo staff reporters Autavius Smith and Natasha Berrios Laguerre.