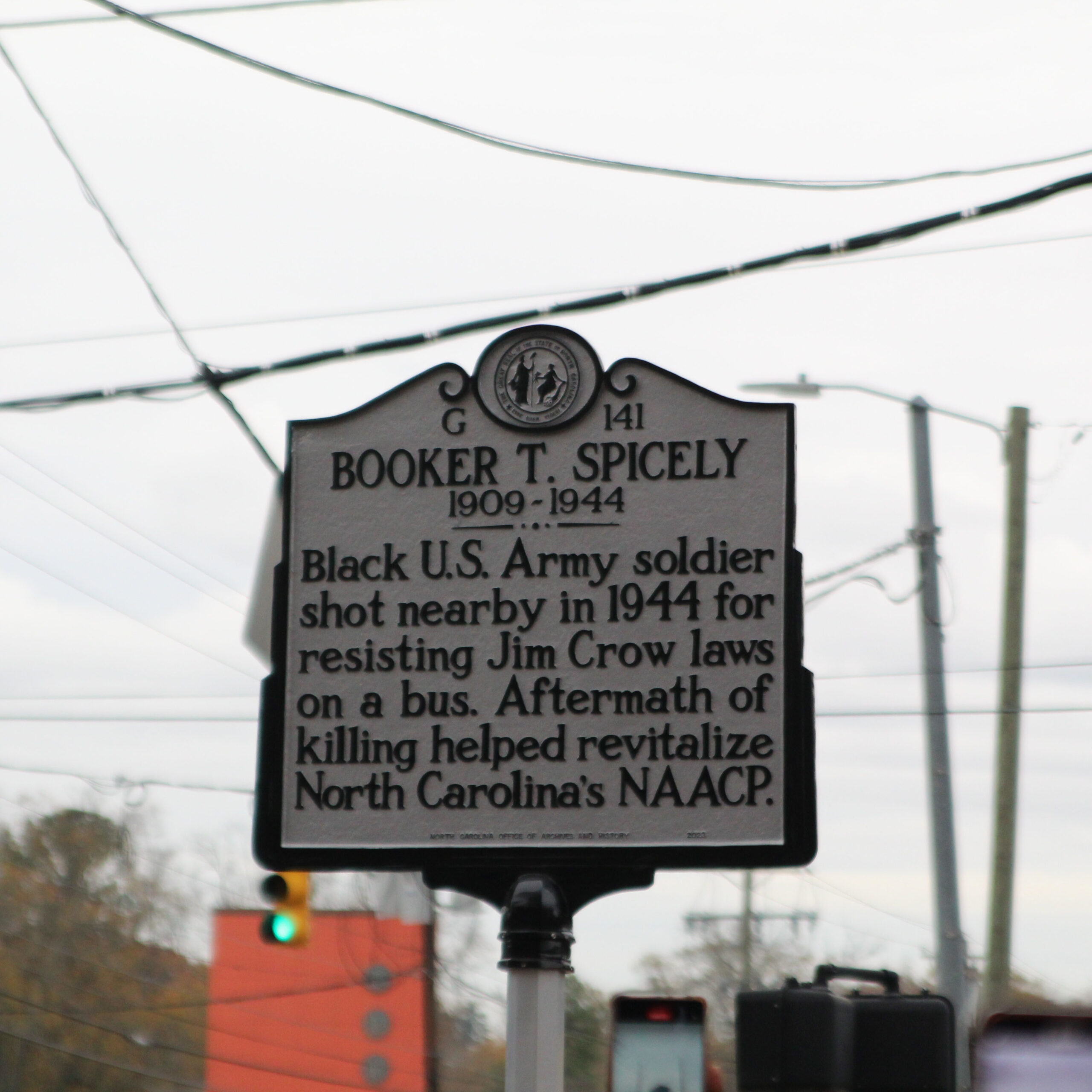

On Dec. 1, 2022, a state historical marker commemorating the life of Pfc. Booker Thomas Spicely was unveiled at the N.C. School of Science and Mathematics. Over 20 members of Spicely’s family joined the Durham community to witness this historic recognition.

Spicely was an educated 34-year-old Black man who had volunteered to serve in the U.S. Army in 1943 during World War II. He was born on Dec. 1, 1909, in Blackstone, Va., to Lazarus and Alberta Spicely.

In July 1944, while stationed at Camp Butner, N.C., Spicely decided to board a bus for Durham. According to various sources, he wanted to spend his leave in Hayti, Durham’s flourishing Black community, “Black Wall Street.”

During the ride, a few White military officers boarded the bus, prompting many of Spicely’s Black counterparts to move to the back. Under Jim Crow, people of color were assigned to the rear while White Americans sat in the front.

But Spicely complained and asked: “Aren’t I just as good to stop a bullet as you are?” Implying the equal treatment he should receive as an officer of the Army.

After Spicely protested to the White bus driver, Herman Lee Council, against the segregationist Jim Crow law, he relented and moved to the back of the bus. According to witnesses, Spicely later apologized to Council, possibly sensing the danger he had placed himself in, but it was too late.

When he got out from the rear door of the bus at the corner of Club Boulevard and Ford Street (now Berkeley Street), Council fired two shots at him with a .38 caliber pistol. One passed through Spicely’s chest and hit his dog tag, the other hit his liver.

While Council continued his bus route. Spicely was transported to nearby Watts Hospital, now the N.C. School of Science and Mathematics. Due to the color of his skin, he was refused service. Critical lifesaving time was lost and by the time he arrived at Duke Hospital, he was pronounced dead.

An all-White jury acquitted Council after just 28 minutes of deliberation, deeming the shooting as an act of self-defense.

The historical marker is especially significant because it is the first in North Carolina to make use of the words “Jim Crow” in the sentence: “Black U.S. Army soldier shot nearby in 1944 for resisting Jim Crow laws on a bus.”

At the unveiling Reid Wilson, secretary of the N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, didn’t shy away from this fact.

“Out of 1600 markers, this is the first [to mention Jim Crow laws] … and it will be more,” Wilson said.

The Booker T. Spicely Committee Chair, James Williams, said this moment in history was among many during the “Double V campaign.” Launching in 1942, the message stood for “Victory Abroad and Victory at home.” In the campaign Black service members demanded equality at home while fighting against fascism in Europe.

“He asked reasonable and sensible questions,” Williams said. “He challenged the system … and it cost him his life.”

Protest and outrage in the Black community after the shooting strengthened North Carolina’s chapter of the NAACP.

After Council’s innocent verdict, Spicely’s life and murder began to fade from memory. Council returned to his employer and would never be held responsible for his actions. He died in a nursing home in 1982.

But in the 21st century: Scholars, activists, and veterans, including Williams and N.C Central University’s Stephen Valentine, would bring awareness to what occurred in 1944.

In January 2023, responding to the painful Spicely tragedy, the Duke Energy Foundation awarded a $100,000 Booker T. Spicely grant to NCCU’s law clinic for veterans. In September the law school held the Booker T. Spicely Symposium in NCCU’s Law School.

Lincoln Thomas Spicely, Spicely’s nephew, who shares the same middle name as his late uncle, said that the unveiling of the marker has a significant and positive impact on both the family and the community.

“What happened many years ago shouldn’t have been done,” said Spicely. “I am grateful …”